Former Kansas track great Wes Santee dies at age 78

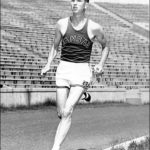

Kansas University track great Wes Santee is shown in this 1954 photo. Santee died Sunday at the age of 78.

Wes Santee, former Kansas University track star and Olympian, died Sunday morning at the age of 78.

A native of Ashland, Santee had been battling cancer.

Santee set the world record in the outdoor 1,500 meters in 1956, the indoor mile record twice (1954 and 1955) and the indoor 1,500-meter record (1955). At one point, Santee had run three of the world’s four fastest mile times.

Santee was named the nation’s most outstanding athlete by the Helms Foundation in 1953. A retired colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps, Santee was a 1950 graduate of Ashland High, for which he was a two-time state champion in the mile run and a state champion in cross country.

“I know he has had peace while fighting this battle with cancer,” said fellow KU legend Jim Ryun, who spent time with Santee this past September at a football game at Memorial Stadium. “He was not a quitter, by any stretch of the imagination. Wes attended every track meet he could, never missing the Kansas Relays.”

Santee, John Landy and Roger Bannister were the subjects of Neal Bascomb’s popular book, “The Perfect Mile,” an account of the three runners to become the first man to break the four-minute mile. Bannister broke the barrier on May 6, 1954, with a time of 3:59.4. Seven weeks after that, Landy broke Bannister’s record. In 1955, Santee posted a mile time of 4:00.5, which would stand as his best.

“I about kicked over the AP printer the day Roger Bannister broke 4:00 because I had convinced myself that belonged to Wes,” former Journal-World executive editor Bill Mayer said. “He was so close so many times. If KU had not had a loose and soggy cinder track for one Kansas Relays solo effort, he’d have made it.”

In what many consider his greatest achievement in college, at a 1954 meet against the University of California at Berkeley, Santee won the 880 yards in 1:51.5, the mile in 4:05.5 and ran his leg of the mile relay in 48.0.

A silhouette likeness of Santee, running with his signature forward tilt, stands by the cross country course at Rim Rock Farm. He was inducted into the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame in 2004 and the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame in 2005.

“Wes Santee was one of KU’s all-time greats, not just in track and field, but in the history of Kansas athletics,” KU interim athletic director Sean Lester said. “He loved KU, and the entire Kansas family will miss him. Our hearts go out to his family.”

Said Kansas head track coach Stanley Redwine: “Wes’ success is a huge part of the KU tradition. He will be missed by the KU family, and our prayers and thoughts go out to his family.”

Santee grew up on a farm in Ashland and told the Journal-World in 2005 that at certain times of the year his father often pulled him from school at noon to put him to work. After everyone had gone to bed, Wes said, he’d turn on a kerosene lamp and get up to date on his school work.

He reflected on a stormy relationship with his father: “We’d be working on the field and it would be time to go back to the house. Instead of riding in the truck with him, I’d run back in because I didn’t want to be with him. That’s just the way it developed.”

In the same interview, Santee noted that Bannister had the help of countrymen serving as rabbits for him on his path to breaking the four-minute milestone.

“Can you imagine someone from Missouri helping someone from Kansas by being a rabbit for him? But you have to give the credit to Bannister,” Santee said. “He was first.”

As a 20-year-old college sophomore more accustomed to running shorter distances, Santee made the 1952 U.S. Olympic team in the 5,000. He was the best American at 1,500 that year, but Amateur Athletic Union officials banned him from competing for the Olympic team in that event because he already had made the team in the 5,000. He did not earn a medal in Helsinki, Finland, that year.

It wasn’t the last of his trouble with the AAU, which ruled him ineligible for amateur competition for allegedly accepting too much expense money from meet promoters. A U.S. senator lobbied for Santee, but a court ruled that the AAU had the power to ban him because of its control over amateur sports. It prevented him from running in the 1956 Olympics.

Married three times, Santee is survived by his daughter, Susie; his two sons, Edward and Bob; his sister, Ina May Walsh; and seven grandchildren.

With daughter Susie among those looking after him, Santee spent his final days at his cabin on Lake Eureka on the eastern edge of the Flint Hills.

Susie said Saturday that she told him to turn his head to look out the window: “He saw the water and smiled a huge smile.”