The great corrective device: Mamet on ‘Race,’ ‘Theatre’ and talking walrus

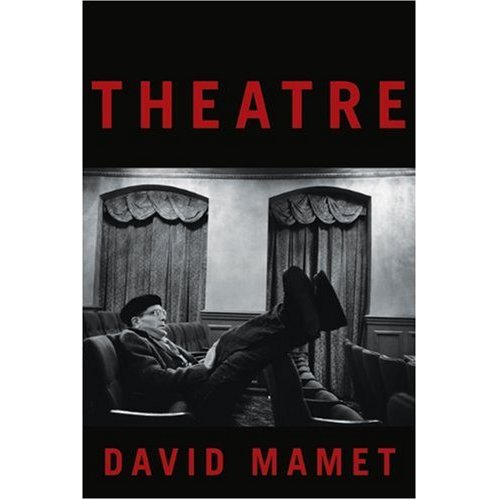

David Mamet continues to contribute to both the world of film and theater. He is also the author of the new book “Theatre,” which analyzes the audience of live performances.

New York ? Early this summer, David Mamet turned on the telecast of the Tony Awards, for which his play “Race” had received a nomination for best featured actor. After a few minutes, and the long kiss between host Sean Hayes and “Promises, Promises” co-star Kristin Chenoweth, Mamet had had enough.

“I was kind of disgusted, I must say,” he says during a recent interview from the dining room of the Upper East Side hotel where he stays during the Broadway run of “Race,” scheduled to end Saturday. The Tonys, he adds, remind him of Constantin Stanislavski’s comment on a production he disliked: When the talking walrus comes on, it’s time to go.

“I don’t want to see a talking walrus,” Mamet says. “And I don’t want to see two actors on stage kissing each other to death.”

Verdict handed down, the 62-year-old playwright resumes his late-morning breakfast of scrambled eggs and decaf cappuccino as he discusses the theater and “Theatre,” his new book. His salt-and-pepper hair is closely shaved, his glasses large with thick rims. He is dressed for heat, in a white cotton jacket and flowered shirt. In his quick, rounded Chicago rhythm, he swears like a real estate agent — in a Mamet play — and philosophizes like a rabbi.

Best known for “American Buffalo,” “Glengarry Glen Ross” and other plays, and for the screenplay of “The Untouchables,” Mamet is a brand name for punching, profane dialogue; for stories of betrayals and reversals; for questions about conscience and the meaning of order. Man is cruel in love and work, a predator, but not hopeless. As he writes in his current book, “We are doomed by our own nature, but grace does exist.”

He calls the Tonys “the Chamber of Commerce” of the stage business, but that’s almost a compliment from a man who has rejected his “brain-dead liberal” past. “Theatre” is a kind of free market manifesto for drama and on the dock are Marxism, psychoanalysis, state-supported theater and Stanislavski, the innovative actor and director whom Mamet admired as a “talisman” long ago, but decided didn’t make any sense.

Mamet’s book is a rejection of abstraction and a call for actors to leave out the personal drama and just say the lines. His goal is grand, yet modest: “If it (the book) saves one young student a trip to graduate school, or an attempt to parse the Stanislavskian trilogy, I will not have lived in vain.”

Changing audience

In “Theatre,” Mamet offers a sketch of the changing, but irreplaceable audience. In the 1950s, he writes, theatergoers tended to be “literate, middle class, largely Jewish,” not just attending the works of Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, but also analyzing them, perhaps changing because of them. They were loyal, ongoing attendees, with high expectations and a general knowledge of contemporary drama.

Now, Mamet says, the typical Broadway theater fan is a tourist or “wealthy vacationer” who asks for little more than to be entertained. You might have found one at a recent matinee performance of this year’s Tonys champ, “Red,” when audience members repeatedly held up camera phones to snap pictures even as the characters on stage agonized over the tensions between art and commerce.

Mamet does not sympathize. The audience remains the “great corrective device” and it’s the artist’s job to keep ahead. He speaks of a concert given by his wife, actress-singer Rebecca Pidgeon. Among the crowd was a bachelorette party, “all getting drunk,” putting on a show they seemed to enjoy more than the one they were supposed to be attending. Pidgeon stopped playing, summoned the bride-to-be — who had an inflatable phallus strapped to her back — and sat with her on the stage.

“‘Young lady, come here,”‘ Mamet recalls his wife saying. “‘I’m going to give you good advice on having a marriage,’ and started giving her marriage counseling advice. And everybody became quiet. ‘I think you’re fine. Now, go back and I’m going to sing some more.”‘

Critics have given mixed reviews to Mamet’s current play. But no one laughed at the wrong time during a recent performance of “Race,” a legal drama about a wealthy white man charged with raping a black woman. The plot is spiced by such vintage Mamet takes as “Jews deal with guilt; blacks deal with shame” and “Someone who hits his first wife will hit his second wife. You know why? Because he’s a wife beater.”

The educated and the curious attended, from 40-year-old Kelly Gibson of Washington, who found the play entertaining even if she had never heard of Mamet, to Roland McFatridge Smith, a 74-year-old retiree from Houston who has seen enough Mamet to decide that “Race” was not among the best.

“It’s an ‘issue’ play,” Smith said. “I’m not totally against issue plays, but some of the situations seemed forced, like he was following some kind of recipe.”

Turning point

Mamet, born in Chicago and now based in Los Angeles, counts himself among the nonfollowers, a troublemaker in school who found a home in the arts, calling outsiders such as himself “the employment pool of show business.” Even his theater book is a spot of mischief, a diversion from other projects that made him feel — as he so often has felt — like he was playing hooky.

“The idea of the non-assigned thing appealed to me,” he says.

Admittedly no good as an actor, he took up writing instead. His earliest plays were very like and unlike his later work. From the start, it was all about two or three people, arguing, with conspicuous pauses. But there was little story beyond the arguing and the dialogue was sometimes the kind of precious talk that would have been laughed out of the offices of “Glengarry Glen Ross.”

“You’ve got to live and learn,” Mamet says. “Everybody starts out writing the laundromat play, the park bench play, the boy and girl don’t get along play.”

The turning point came in the mid-1970s with “American Buffalo,” his classic set in a Chicago junk shop. When Mamet started writing, it was a “tone poem,” beautiful to read, but unbecoming to watch. Director Gregory Mosher, Mamet recalls, wanted him to “actualize the plot.”

“The hardest thing I had ever done was to write a plot,” he says. “Instead of making a magnificently touching portrait, I made it into a play. … I saw the light, as it were. You could write interesting tone poems, or you could actually teach yourself to write drama.”

“One of the many pleasures of ‘Buffalo’ was the early lesson that you can’t go wrong if you hang your hat on the story, however buried it may be in all the dazzling words,” says Mosher, who finds that Mamet’s vision has become even bleaker than the harsh portraits of his early years.

“In ‘American Buffalo,’ when a guy says, ‘There is no law,’ we understand the sentiment to be a sociopath’s rage. True maybe, but to be resisted. In the more recent work, including, of course, ‘Race,’ a lawless world is a given, and resistance a sucker’s game. This is a much darker, and of course completely legitimate, view of the world. It is usually expressed in comic form — ‘Candide’ is the great example — and so it is with David’s plays.”