Finding out who you are

DNA testing kits help people discover origins, research health

Alice Lieberman always defined herself as a full-blooded European Jew until her DNA told her otherwise.

A few months ago, she purchased a partly self-administered DNA testing kit for $180 from Family Tree DNA. She used the enclosed swab to scrape a few cells from the inside of her cheek, placed the specimen in a plastic tube and sent it off to the Family Tree DNA lab.

A few weeks later, she found out something she might never have known.

“The thing that surprised me was how much Western European was in there … the English and the Irish,” said Lieberman, a Kansas University professor of social welfare. “I feel so identified as being a European Jew that it just struck me as odd.”

But Lieberman also had confirmed some things she’d always believed. Her ancestors originated in Asia, and many later settled in Eastern European countries such as Austria, the Czech Republic and Hungary. She also confirmed her place in the Ashkenazi Jewish tribe.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is who I am,'” she said, remembering the moment she learned her results.

Lieberman is one of a growing number of people, locally and nationally, who are testing their own DNA to learn about their ancestry and, essentially, themselves.

Exponential interest

The leading company in the field, Family Tree DNA, sells 30,000 kits every year. So far, about 40 of them have been to people in Lawrence. President Bennett Greenspan said his business has grown “exponentially” since its humble beginnings in 2000.

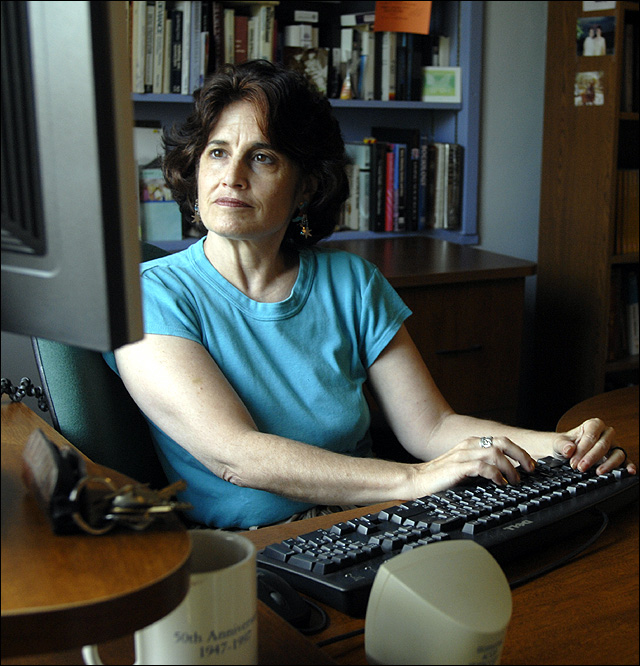

Alice Lieberman, a Kansas University professor, recently bought a DNA testing kit for herself and got some surprising results about her ancestry. The kits are becoming increasingly popular for those tracing family trees and researching health questions.

He also said Family Tree DNA was the first company to sell DNA testing kits for genealogical purposes.

In 2005, the company struck a deal with National Geographic to promote personal DNA testing. That’s how Lieberman found out about it.

But genealogy isn’t the only thing revealed by personal DNA tests.

Chuck Bryceland, of Bronxville, N.Y., recently tested his DNA for health purposes. He bought two tests – one to examine his genetic propensity for heart disease, another to screen for his body’s ability to absorb nutrients – after spotting them on the shelf in a drugstore while traveling.

He paid $199 for one test and $99 for the other, which told him that he is unlikely to develop heart disease but that his body poorly absorbs Vitamin B. Since then, he’s been campaigning to get his wife, his parents and other family members to take the tests, too.

“If there’s information out there that we can use to help our health, then why wouldn’t I take it?” Bryceland asked.

How it works

Michael Crawford, a Kansas University professor who specializes in biological anthropology, said that the technology behind these at-home testing kits has been around for 20 years.

How it works is highly complicated.

Crawford explained that scientists first gather the human cells. Then they extract the DNA, purify it and chop it into fragments.

Those fragments are examined by scientists, who look for mutations in specific genes. People who share common mutations are considered to be related.

“I use molecular genetics to reconstruct human history,” Crawford said. “We’ve pretty well reconstructed the human diaspora … 100,000 years ago, humans began migrating from Africa into Europe, Asia, etc.”

Crawford even tested himself with his lab’s DNA sequencer before the practice was common. What he found didn’t surprise him; his ancestors came from Russia and Scotland. But what does surprise him, even after years of research, is the unchanging nature of DNA.

He cited the case of Thomas Jefferson’s DNA as an example.

“Going from Thomas Jefferson’s grandfather to the current generation, there is only a single mutation in the Y-chromosome, which is kind of exciting,” Crawford said.

While genes passed from father to son are fairly reliable, the genes in women aren’t as easy to decipher. For example, Lieberman said that she’d like to find out whether or not she is a Cohen.

A Cohen is, in religious terms, a member of a Jewish tribe who is a direct descendant of Aaron, the brother of Moses. They were once the high priests of Judaism.

“I think it would be fabulous to find out,” Lieberman said. “I did everything a woman can be tested for, but I don’t know.”

Lieberman will most likely never know, because the Cohen marker doesn’t show up in female DNA.

Family history

Ardie Grimes, a librarian and genealogist who lives in Baldwin, said she bought her husband a DNA testing kit because she knew her DNA wouldn’t yield many results.

She said she had been researching his family history when she hit a “brick wall.”

“We knew very little about the paternal side of the family, so I was hoping that the DNA testing would give us insight into that, and as it turns out, it really hasn’t,” Grimes said.

Her husband Greg’s DNA results told them little they didn’t know and only yielded one match with a person on Family Tree DNA database.

A match on the database means that there’s someone else with DNA similar to yours. The matches can be strong or weak, but they usually mean that the two people share common ancestry.

More about personal DNA testing

Grimes said there were some matches she found going back 28 generations. That may be interesting, but it didn’t help her construct a family tree.

“Well, I don’t have any research from 28 generations back,” she said. “So I guess I was hoping that we would find some immediate ancestors within three or four (generations) that we could share data with.”

That hasn’t happened yet, but in the future, as more and more people place their genetic information on the Family Tree DNA database, matches should become more common.

At least that’s what Lieberman’s hoping.

She said aside from finding out she’s more Western than Eastern European, her DNA test didn’t tell her a whole lot.

“I check periodically to see if anything’s been added in terms of new matches, and I’m looking for higher resolution matches than I may have,” Lieberman said.

Still, she said, testing her DNA “may well be worth it in the long run.”