Dig uncovering facts about earlier human life

KU working on excavation in northwest Kansas

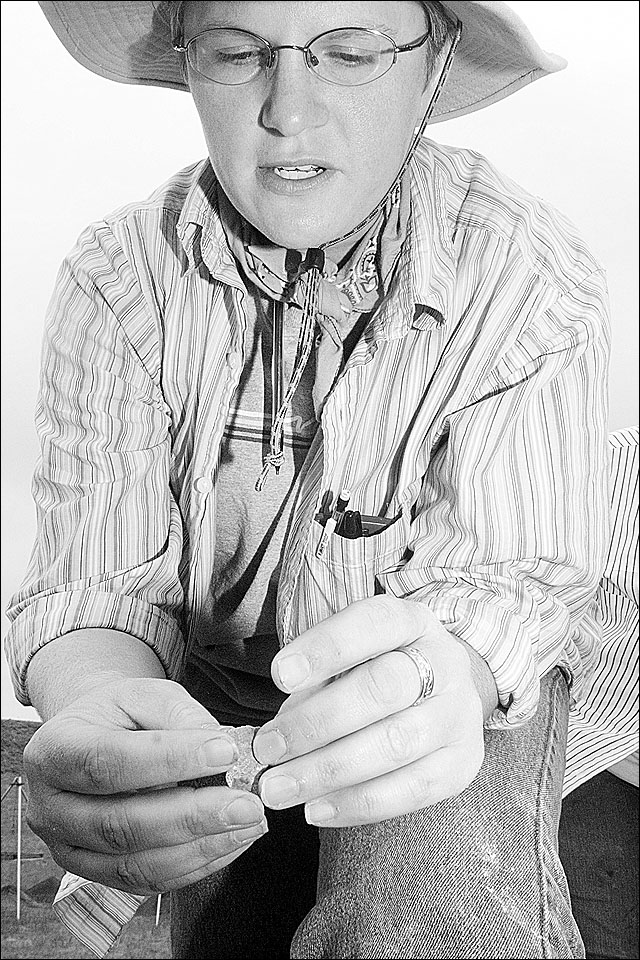

Janice McLean, a Kansas University master's student, examines a stone flake found at an archaeological dig site near Kanorado. The flake, possibly a piece of a tool, is typical of the finds at the site, which may be one of the earliest human sites found in the Great Plains.

Rolfe Mandel has spent parts of three summers at an archaeological dig site near Kanorado, and he’s still fascinated.

The site, he and others think, once was home to springs that made it attractive for early inhabitants of Kansas.

Marks on mammoth and camel bones found there indicate humans might have been on the Great Plains 700 years earlier than previously thought, but definitive evidence – in the form of a man-made tool from the era – has proven elusive.

“That’s still a mystery, and we’re going to pursue it,” Mandel said. “We’ll be going back next year.”

Mandel, an archaeological geologist with the Kansas Geological Survey, and Steve Holen, curator of archaeology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, are leading the excavation of the site.

A team from KU, the Denver Museum, the Kansas Archaeological Assn. and the Kansas Archaeology Training Program of the Kansas State Historical Society spent much of June at the site near the Kansas-Colorado border in rural Sherman County.

“We found a lot of artifacts,” Mandel said. “It was a very productive excavation.”

A paleontologist from the Denver Museum first came to the site in 1976, when artificial creek channels created by the Kansas Department of Transportation caused mammoth and camel bones to become exposed.

Holen decided to return to the location after seeing some of the artifacts collected.

This year’s dig took on new importance based on radiocarbon dating results completed in February. The tests showed that the mammoth and camel bones found at the site dated back to 12,200 years ago.

Kim Kilmartin, a sophomore at Baker University, sifts through dirt collected at an archaeological dig site near Kanorado, hoping to find flakes of bone or rock that might help date the site. Researchers think the site could be one of the oldest signs of humans found in the Great Plains.

The bones appear to have tool marks made by humans, who probably broke the bones apart to extract marrow for food or to make bone tools, Holen said. If workers can find tools in the same area where the bones were found, it could disprove the widely held belief that humans arrived in North America around 11,500 years ago.

“The best thing we could find is a very patterned artifact – one that’s obvious humans made it,” Holen said. “It would change the way we think about early humans in North America.”

That hasn’t been found so far, but Holen and Mandel hold out hope that it could happen in the future.

Other evidence

Even if evidence pushing back the arrival of humans in the plains isn’t found, the site is still one of the best-preserved campsites for early plains people, the researchers said.

Pieces of tools and a bead from the Clovis era – from roughly 10,800 years ago to 11,500 years ago – have been uncovered. In the past, most Clovis-era artifacts have been found away from campsites, such as arrowheads found in fields, Mandel said.

And this year’s dig uncovered artifacts from the Folsom era, roughly 12,300 to 12,800 years ago. Those artifacts included several scrapers used to clean bison hides, which meant there must be a bison kill site nearby.

“It’s a hot spot,” Mandel said.

Tedious work

This year’s dig included shifts of about 50 volunteers at a time.

They were spread across three sites at the dig, all in the side of a bed of a former creek. Each excavation site was divided into grids with 1-meter-square sections.

Using levels and tape measures, workers scraped off 5 centimeters of dirt at a time, keeping an eye out for rock and bone. They sifted each section of dirt through screens to make sure no artifacts go undetected.

When an artifact is found, it is placed in a bag, and KU graduate students use surveying equipment to pinpoint the exact location where it was uncovered. Those artifacts are now at the Denver Museum for analysis.

“It’s exciting every day,” said Janice McLean, a graduate student who worked on the project. “You find one really exciting thing, and you can live off that for three or four days.”

Kim Kilmartin, a Baker University sophomore from Topeka, was another worker. She got interested after completing an internship in a processing lab at the Kansas State Historical Society.

“It’s actually a lot more fun than it looks,” she said. “In the lab, you actually know what you’re looking for. Finding it in the field is very cool, even if it’s the smallest stone flake or bone fragment.”

Mandel said he was anxious to get back in the field next summer to see what else the site might hold.

“This,” he said, “is tantalizing.”