U.S. bishops come under increasing fire for new policy on child-abusing priests

The reforms were meant to restore trust and end a crisis.

But three months after America’s Roman Catholic bishops promised to aggressively discipline priests who molest children, resistance to their policy is intensifying and the plan could be coming undone.

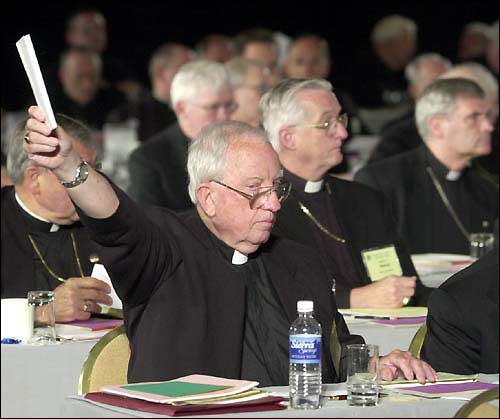

An unidentified bishop holds up a ballot during the voting on the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops meeting in Dallas, in this June 14 file photo. Three months after U.S. Roman Catholic bishops promised reforms to aggressively discipline priests who molest children, resistance to their policy is intensifying.

Parishioners are rallying behind accused priests. Clergy are suing alleged victims and complaining to the Vatican. Experts in church law are questioning whether the plan violates priests’ rights.

Leaders of religious orders have accused the bishops of ignoring Catholic teaching on redemption and are allowing some abusers to continue their church work away from children.

“It is unraveling,” said the Rev. Richard McBrien, a liberal theologian from the University of Notre Dame.

“I don’t think anybody knows where we’re headed,” said Philip Lawler, a conservative and editor of Catholic World Report magazine.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops insists its members are on the right track. Officials point to dioceses nationwide that have expanded their lay review boards, hired people to help victims and suspended accused priests.

“If anything, the majority of the signs have been of a readiness to put the charter into effect,” said Monsignor Francis Maniscalco, a spokesman for the bishops’ conference.

However some bishops have delayed putting parts of the plan into practice, such as ousting abusers from the priesthood, until the Vatican weighs in, and several analysts predict the Holy See will reject it. Rome’s approval is needed to make the policy binding on U.S. dioceses, otherwise the policy approved June 14 in Dallas is simply a gentlemen’s agreement.

The bishops have said that even if the plan is voluntary, no church leader would dare ignore it in this climate of public anger associated with mishandled abuse cases. The prelates formed a lay committee, the National Review Board, to evaluate whether dioceses were in compliance.

Yet the man the bishops recruited to head the panel, Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating, is already under attack from within the church, even before he stages his second meeting with the commission Monday.

The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Council of Priests said Keating was “more concerned with manipulating the public’s emotions than seeking the truth.” Keating’s own prelate, Archbishop Eusebius Beltran, accused the governor of encouraging Catholics “to commit a mortal sin” when he said parishioners should switch dioceses if their bishop fails to properly address abuse.

Rank-and-file Catholics are directing their anger at bishops.

At St. Rose of Lima Church in Cleveland, where the Rev. James Viall was accused of abuse and suspended, parishioners spoke up for the priest and jeered at diocesan administrators who urged compassion for victims.

Members of St. John Parish in Worcester, Mass., have rallied around the Rev. Joseph A. Coonan, who was suspended for abuse claims from before he was ordained.